Dear friend,

By the time this letter reaches you, I will know.1

Any newsletter—or any piece of writing, for that matter—goes through this shape-shifting kind of time travel. I don’t usually schedule my newsletters. The moment of knowing when they are complete and ready to be released is usually unpredictable, and when it arrives, urgent.2 But today, I am writing this letter to you on Tuesday, March 18th. When it reaches you, it will be a little after 9:45 am on Wednesday, March 19th.

This time is specific for a reason. Tomorrow morning, I have a follow-up appointment to see if I meet diagnostic criteria for a condition I may have been experiencing all my life.

When you seek out diagnosis on your own terms, so much of it is seeking external validation. Tell me there is a name for this. Peer review my extensive research. I am trying on this narrative. Will you validate it for me? I pulled the Lovers reversed this morning, which encapsulates this yearning quite well. Pulling it was less validating and more activating, especially in this excruciating in-between waiting time. I understand its bitter medicine, even if I want to spit it out.

The difficulty in relinquishing control and sending this letter forward in time is that as I’m writing, I don’t know what the answer will be. I may not get the answer I’m seeking. I might know and not know in another way.

Last week, I stumbled across the phrase: the site of so many ontological cave-ins.3 Individually and collectively, literally and figuratively, so much is caving in, so much is beginning, and ending, and in-between, all at once. This morning, across the ocean, it was reported that Israel violated the ceasefire and launched airstrikes over the Gaza Strip, killing over 400 Palestinians and wounding over 500. As I write, rescuers are searching the rubble for who may be remaining. Writing this I am sick to my stomach with grief and turmoil and paralysis. I know the actions: continue doing the work, continue the fight. The actions feel not enough and too much all at once; like as the world stops I must stop too or launch myself into the sun.

The tension of the in-between. The tension of grief. The tension of us and I and body and mind. The tension of not knowing. When I pluck the string it thrums wildly, over and over before going slack.

Astrologically, we are in a time of in-between tension too. As I write, we are in between eclipses. Last week, we experienced a lunar eclipse in Virgo conjunct the South Node, and next week, we will experience a solar eclipse in Aries.4 If you are completely unfamiliar with astrology , the gist of what you need to know is: eclipses are portals of unraveling and intensity. Think power outages, or releases. Where eclipses are in the sky depends on the positioning of the nodes of fate (the North and South nodes), which are polar points in the sky where the moon’s path crosses the sun’s ecliptic path. The South Node (often called the tail of the dragon) represents karmic memory, our histories/pasts, patterns, and what we are releasing. The North Node, in contrast, is characterized by a certain hunger or expansion. Currently, the nodes are transitioning from an Aries-Libra polarity to a Virgo-Pisces polarity; hence one eclipse being in Virgo, and the other in Aries. Even the nodes of fate are in transition.

In the midst of all this: a Venus retrograde, a Mercury retrograde, and another thing we are awaiting: the arrival of Aries season, and with it the Spring Equinox and Western astrology’s zodiacal new year. That will be this Thursday. Maybe, when you read this, Thursday will be tomorrow. Maybe it will be yesterday. Or maybe days or months or years in the past, with all the collective wisdom and coherence that hindsight brings. But for now, I am writing to you from that strange, eerie, excruciating middle.

A three year arc has assembled a schema in my mind. I don’t yet know what the schema is for. Many Tarot practitioners use numerology to calculate the Tarot Card for the Year. As an example, this year:

2+0+2+5=9.

The 9th card in the Major Arcana is The Hermit. In the card, an old, wise crone figure stands in the snow. They are wrapped in a hooded cloak and carrying a walking stick and a lantern for their journey. Their gaze is cast downward and slightly forward; it is implied that under the faint light of the lantern, they can only see what is right in front of them.

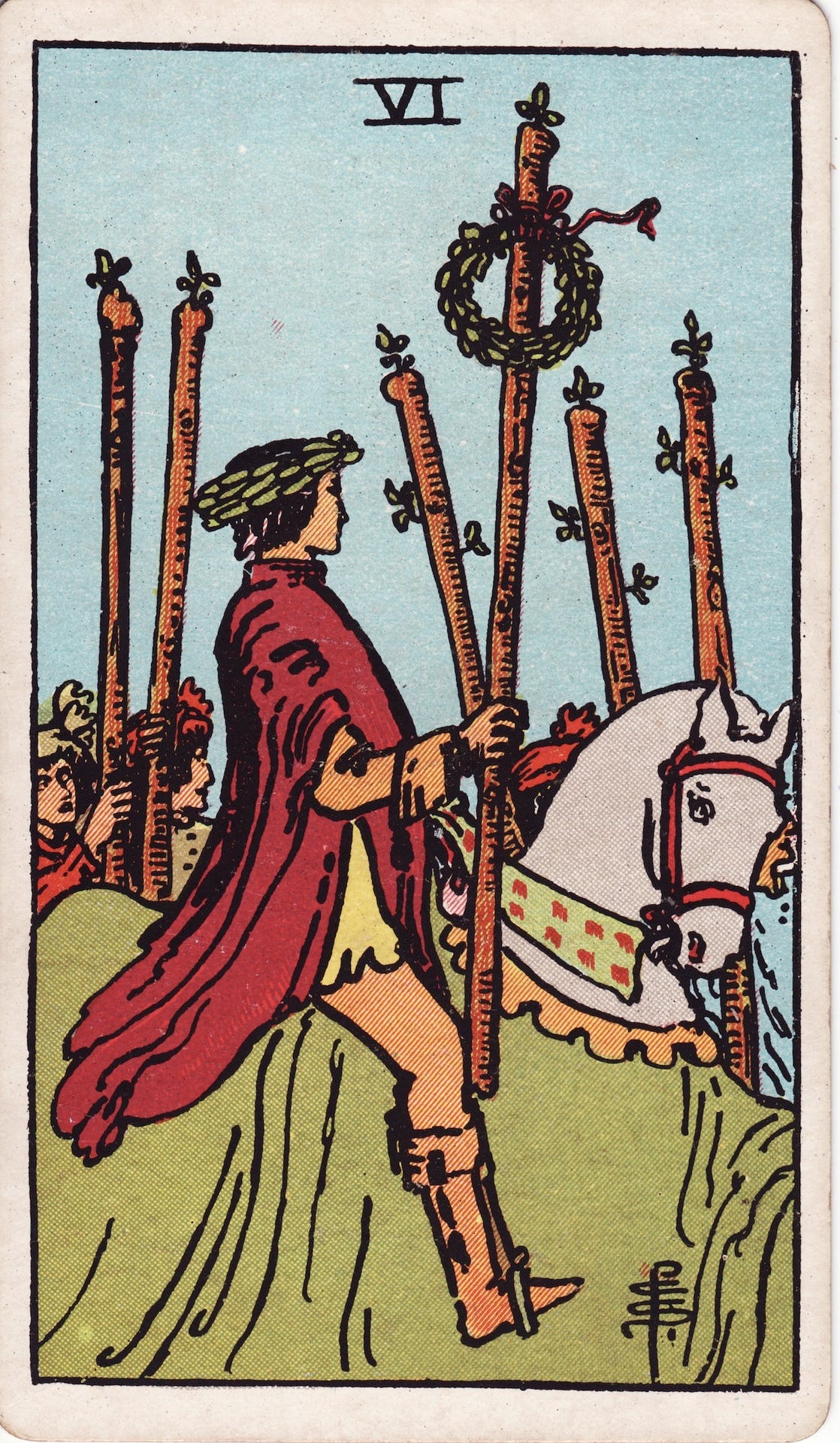

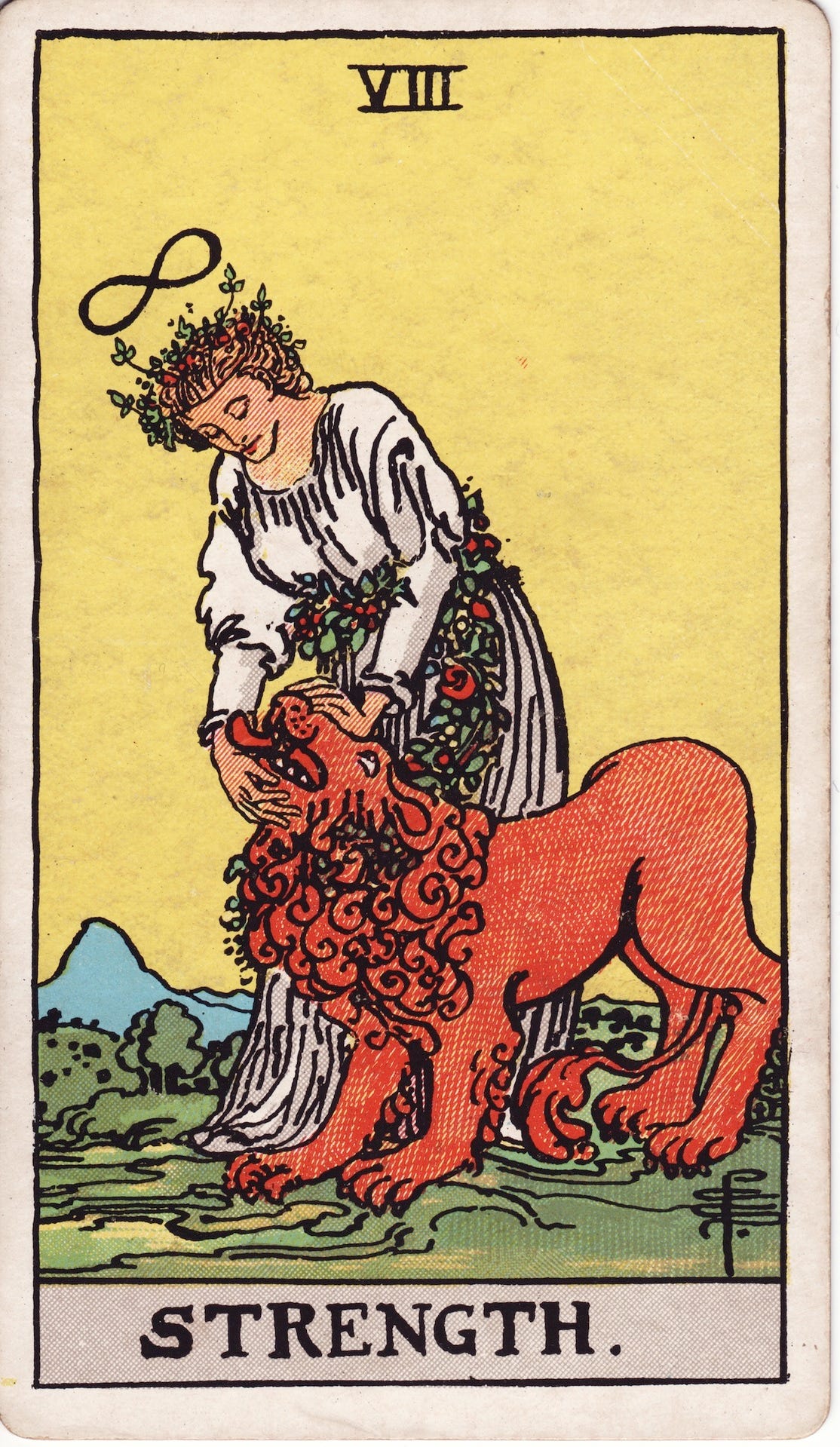

From there we stretch back in time. 2+0+2+4=8. Strength. Leo. The lion. Back further: 2+0+2+3=7. The Chariot.

I remember the in-betweens of these years vividly. I remember 2023 to 2024, Chariot to Strength, quite well; the hunger, the desperation, the longing to burn brightly. Now I am just tired.

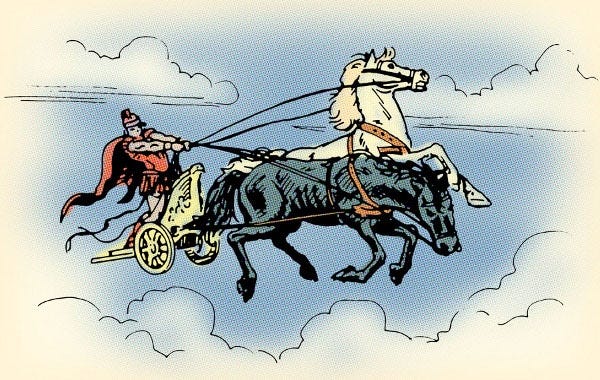

The Chariot recalls Plato’s tripartite theory of the soul: the Chariot allegory. The Chariot tarot card. In Phaedrus, Plato uses a chariot to figure his proposed three parts of the soul: a charioteer (”man”/”reason”) drives a winged chariot led by two horses. The dark horse is the sensitive, material human appetites and needs; the white horse is the “spiritual soul” (thymos). The dark horse (the body, the material, it seems) is notably characterized as “bad,” and the white horse as “good”.5 Plato writes:

Of the nature of the soul, though her true form be ever a theme of large and more than mortal discourse, let me speak briefly, and in a figure. And let the figure be composite—a pair of winged horses and a charioteer.

The right-hand horse is upright and cleanly made; he has a lofty neck and an aquiline nose; his colour is white, and his eyes dark; he is a lover of honour and modesty and temperance, and the follower of true glory; he needs no touch of the whip, but is guided by word and admonition only.

The other is a crooked lumbering animal, put together anyhow; he has a short thick neck; he is flat-faced and of a dark colour, with grey eyes and blood-red complexion; the mate of insolence and pride, shag-eared and deaf, hardly yielding to whip and spur. Now when the charioteer beholds the vision of love, and has his whole soul warmed through sense, and is full of the prickings and ticklings of desire, the obedient steed, then as always under the government of shame, refrains from leaping on the beloved; but the other, heedless of the pricks and of the blows of the whip, plunges and runs away, giving all manner of trouble to his companion and the charioteer…

The chariots of the gods in even poise, obeying the rein, glide rapidly; but the [mortals] labour, for the vicious steed goes heavily, weighing down the charioteer to the earth when his steed has not been thoroughly trained:--and this is the hour of agony and extremest conflict for the soul.

In the end, it is the dark horse that “ruins” it all, by charging toward what it needs.

The Parable of the Egg

Remember this— Even the ancients played with sock puppets. After the Chariot comes the Fall, says Plato, playing with two socks. Socrates and Phaedrus. Last year was a Chariot year: 2+0+2+3 =7, the seventh arcanum, the seventh mystery [and all the sevens of all the elements. Seven cups of water. Seven stones of earth. Seven knives of air. Seven matches, struck with fire.] I am glad to be rid of it. I am sick of sevens and chariots. 2+0+2+4=8. Strength year. I burn for it. I want for eights, and lion, and fire, and swift movement. But I have forgotten. Rachel Pollack figures the 22 cards of the Major Arcana, numbered 0-21, in three lines. 3 lines, 7 cards apiece, not including 0: The Fool: the traveler between realms of cards as you shuffle, the microcosm and the macrocosm, the egg hatching. The egg travels between cards and lines. 8 is the entry to Line 2. 8 is the door to the underworld, led by a lion. Line 1 [Cards 1-7]: Ego. Identity formation, self. I am. Line 2: [Cards 8-14]: Underworld. Fragmentation of self. Who am I? Line 3: [Cards 15-22]: Collective. There is no I. To move from I am to Who am I? is no simple task. No matter if you have lived There is no I. To lose the ego, the story, the ontology, again after the first time, again and again, and again, with no end, is the hardest part. There are parts of us that are so new. And then something happens and it’s new again.

You, The Fool, jump from the driver’s seat. The chariot is ripped apart in the taut atmosphere. As you fall, you think, God, I am so glad I jumped. You think: I am almost flying. You think: Who needs horses? But you have forgotten that The Fool is an egg. You have forgotten that you, vessel, traveler, body-holder are a fragile thing. The body, the egg, splatters on the earth.

(Or: let me tell it another way. You are preparing for a long journey, a trip with your two beloved horses through the woods. One: dark as night; the other: white as snow. They have been with you, your companions, for as long as you can remember. At the other end of the woods there is a destination you have been looking forward to for quite some time. You have spent years crafting the perfect chariot, test-running, patching up the tears, loving on the vessel. Unable to hold in your excitement, you announce your journey to the townspeople. When you depart, they gather to see you off: banners, cheers, triumph, shouts of glory. Your journey begins smoothly: slow, measured [you are a being of reason. You are careful over the bumps]. You have made it a third of the way through your journey. Then: without warning: jolts. You do not see the source. Your dark horse just startles, as if at nothing. Whoa, whoa, you soothe, gripping the reins tighter [it is no use; she continues running]. At first you are a little embarrassed, even without witnesses: you are a good, studied driver. You look around for witnesses to make excuses at. It’s the horse. Your justifications do not help. In fact, she is going faster now. Your white horse protests, whinnies; but even she has no choice but to run along; even she is susceptible to the wildness. When the crash happens time folds over. Iterated again and again, reverberating through your memory, again and again and again. It is always with you. Too loud. Too much. Patterns in repeat, over and over and over

—all at once, an eerie stillness.6 You crawl to what was once your precious, beloved chariot, cracked open, shattered upon rock. In theory, we dismiss the material. But we forget that material is bound up in us. Your lover, who attached the wheels and massaged your sore shoulders after a day of work. Your father, who handed you the beautiful leather reins with great pride. Your mother, who both walked with you through the blueprints and stitched the soft carriage seat. They worked so hard for you. And look what you have done. But there is no time to grieve: the earth shakes, opens. It swallows you whole.)

You had forgotten: or perhaps not forgotten. You had fallen off the horse already, scraped the skin, known intimately the rough kisses of the earth, even come to love them. You had your bruises: You had your proof. The hubris of a lover: to think you know another fully because you’ve explored their skin. But even the earth is a fickle creature.

gone spelunking

After the initial shock, survival mode kicks in. You shake it off. You re-orient. Your eyes adjust to the deep dark of the underworld. You remember your nature: You, crafty, clever. Resilient one. All eggs must crack to be born.

You are dripping in yolk. Some bits dry up and crust; others keep running, dripping onto everything, an evergreen well. You enter the room of eggs. They appear to, at least shell-wise, be intact. There must be something wrong with my shell. Maybe that is why I'm here. But right now, that does not matter. What matters is the fact that you are dripping, everywhere. It is embarrassing. Sorry sorry, you mumble, smearing yolk on the cave walls, hands yellow, sticky, shards of shell stuck in your hair. When the yolk crusts, it is itchy, immobilizing. When it drips, it is embarrassing. You stumble around, leaking, desperately searching for the faucet. At first, you can pass it off as a charming quirk: funny, even. But when you show up day after day, dripping, sticky, then crusty, it gets old quick. It becomes a problem. When you finally locate a bucket of water, you are too exhilarated. You dump the ice cold water over your crusty, dripping body. Icy shock, which has you shrieking, slipping, running. The eggs are unamused. You are still dripping, just in a different way. Look! You screech, dripping all over the floor. Look!

In another of Plato’s soul figurings, thymos is a lion.

the egg transforms from chariot to lion

The difference in images is not so drastic: If you grab onto the lion’s mane and hold the hairs taut, they could be reins. If you pull the mane too tight and the hairs rip from the scalp, there are always more to pull. Still: you miss your horses. Still, the skin cries out, swollen, red.

The Smith Rider-Waite depiction of the Strength card invokes a pastoral scene. Abundant land and a bright sky. Yet, something does not fit: a lion with coiled muscles and a lolling tongue. The lion gazes up with an unreadable expression (Panic? Devotion? Delirium? Something else?) at a woman in a white gown strewn with roses.

Slightly above the crown of her head floats The Alchemical 8. The infinity loop. An 8 turned on its side—the promise, of cycles, of transformations, of looping back around. It is fitting that the entrance to Line Two, the underworld line, is an infinity loop. It is also fitting that it is an 8. The eights in the Tarot—Strength in the Major Arcana; 8 of Swords, 8 of Pentacles, 8 of Wands, and 8 of Cups in the Minor Arcana—are numerological shape-shifters. Portals. When you walk through, you are transformed into another being entirely.

The woman gazes into the eyes of the lion, gently prying open its jaw. It is unclear what her intent is. Maybe it is to tame or cull into “proper” behavior: in more archaic versions of the Tarot, men raise their clubs to strike at the creature. A display of “strength.” This woman’s gaze seems soft, but even the gentlest of touches can cloak nefarious intentions—even if the woman doesn’t know that herself. I think the lion knows this. The back is arched, and the muscles appear to be clenched, as if allowing, yet preparing. The lion knows that it is feared, that it is being examined, that even in the woman’s acceptance it is an Other. The lion also knows that the touch, in this moment, is gentle. It tries to remain still, to relinquish control and settle into her hands, even as every muscle coils in preparation to run.

You think: I wasn’t supposed to be the lion.the lion’s litany: return of the door-keeper

I am sick of you, strategy. I am sick of you, door-keeper, stove-checker, hair-plucker, sheet adjuster, lion-tamer, do you need anything from me, turn your camera on so we can see your pretty face, we’ll hit the ground running on Monday. I am sick of you, snake that coils back round to bite its own rattling tail, disciple of law, and order, and law, and entropy, and fire drill, over and over, I am sick of begging to survive in a way that does not exhaust me, that does not kill us all, I am sick of begging to survive in a way that does.

The morning after the snowfall, I kiss my lover on his way out to the truck. “Be safe,” I tell him. Insurance. Maybe by saying it I will will it. Then: “I am going to go write.”

“Be safe,” he replies. He is being cheeky. But I try, serious, reverent. He’s right. I do need to be safe.

Uncanny, the quiet relief of grief. Like a hand, white-knuckling, scarring the palms, then undone with a snip. Slowly unfurling. Awestruck that the joints bend that way at all.

θυμός [thymos], or the lion contemplates the underworld

The etymology of my father is cyclo + thymos [from Greek] kuklos ‘circle’, 'cycle' + thymos or thumos ‘spiritedness’: physical but *not somatic, assoc. breath or blood - human desire for re - cognition; permanent possession of living man, urge reason + appetite. The etymology of me is my father[+ my mother, etymology : doctor or docere [Latin], teacher; or hælan 'cure; save; make whole, sound, well']. The etymology of diagnosis is diagignōskein [modern Latin, from Greek]; ‘to know thoroughly’; ‘to know apart’; from dia ‘apart’ + gignōskein ‘recognize, know again’. The etymology of etymology is root: etymos [Greek] 'true', 'real', 'actual' + -logia [Greek] study of, speaking of or: is this true? // real? // actual? The etymology of dilution is dīlūtiōn; [Latin] dīlūtus, dīluere ('to wash away, dissolve, cause to melt'), from dī, dis ('away, apart') + luere ('to wash') See lave ['wash, pour']. *compare: deluge. or: bloodline + time + an overwhelming amount of water.

It operates from a kind of scarcity, clenched fist, wound*

nervous system

It sneaks and slips in. In a sense,

]

]

]

]

what’s missing———haunts———I am always finding

language too latefield notes from the tail end of the lion

A drill is burrowing into my skull again. It’s The Hermit, rumbling to return, to come through. I try, but I cannot help my lover assemble the storage. When he comes to find me, I’m burrowed in blankets. I lay my head in his gentle palm. “You’re warm.” I hadn’t noticed.

“Poor baby,” he coos, “Swollen brain.” He massages my scalp. On the crown of my head he draws circles, then alchemical 8s.

How do we rest in the in-between?

I have a body that craves stillness and at the same time finds it unbearable. It’s not a matter of not being able to cope with my own inner landscape; I find that internal world so rich and rife with possibility and discovery. There may be nothing more pleasurable than sitting with oneself, even if you aren’t literally sitting. It’s the rest of it; the way stimulation prods and permeates the body, and the body’s yearning to respond. My body resists becoming an object for the mind’s benefit. It will not be still.

A. is trained in Alexander technique. When my spinal pain was at its peak several weeks ago, he practiced the bodywork on me a few times. The first round, I lay on the floor with my knees bent and feet flat on the floor, as you’re supposed to. The entire time, while I worked and concentrated to clear my mind, all I could think about was the positioning of my knees. How even having them in this “relaxed” position, bent and flat on the floor, I could not bear the weight of holding them up. They wanted to fall over and collapse into some improper form. Not from pain, which was confined to my spine and back—rather, from an exhaustion I could not understand. At times, my body shook, expelling frenetic energy, the valve sealing and unsealing.

There is a pressure cooker sitting on my kitchen counter, which I used this week to make slow cooker apple pie oats for the morning. I plan on using it today to prep some chicken wild rice soup for dinner. There is a valve that seals and unseals at the top. When you unseal it at high pressure, steam will hiss out, spitting into the room. It is not a pleasant sound. But the lid will only open two ways when there is so much pressure contained within: 1) by unsealing the valve, or 2) waiting, patiently, for the organic release.

A part of me is deeply satisfied by the abrupt hiss of the unsealed valve. The reassurance that whatever I am cooking has, in fact, come to pressure—that the pressure exists. And a small release, to let some of it escape. I have to imagine it feels amazing. Sometimes I will flip it on and off for fun—hissing, nothing. Hissing, nothing.

hypothetical scenarios for the entropic exhaustion of the universe

I don’t know where I found it, the phrase, what led me scrambling down another rabbit hole, but I did. Big Crunch. I’d known the theory, but not the name. This article is about the entropic exhaustion of the universe.

This article is about the entropic exhaustion of the universe. A Big Bang’s equal and opposite reaction.

I remember thinking, A Big Crunch must feel great for a universe.

From On a Universal Tendency in Nature to the Dissipation of Mechanical Energy:

The result would inevitably be a state of universal rest and death, if the universe were finite and left to obey existing laws. But it is impossible to conceive a limit to the extent of matter in the universe; and therefore science points rather to an endless progress, through an endless space, of action involving the transformation of potential energy into palpable motion and hence into heat, than to a single finite mechanism, running down like a clock, and stopping for ever.

As in: don’t worry. As in: infinite progress. As in: endless density of matter. As in: fiery consumption, never-ending. An endless progress, through endless space.

So no singularity then. Dark energy drives the endless expansion of the universe, without relief. How does she do it? I want to draw together, cocoon into my own gravity like dark matter.

In The Myth of Sisyphus, Albert Camus writes:

Like great works, deep feelings always mean more than they are conscious of saying. The regularity of an impulse or a repulsion in a soul is encountered again in habits of doing or thinking, is reproduced in consequences of which the soul itself knows nothing. Great feelings take with them their own universe, splendid or abject. They light up with their passion an exclusive world in which they recognize their climate…at any streetcorner the feeling of absurdity can strike any man in the face.

Thymos is a universe. Within that universe, a million little worlds, constellations burning and patterning across deep, un-colonizable space.

When I think of eternal binds of exertion, I think of the myth of Sisyphus. I think of Camus and the absurdity of endless progress, endless expansion. For what? For whom?

The gods had condemned Sisyphus to ceaselessly rolling a rock to the top of a mountain, whence the stone would fall back of its own weight. They had thought with some reason that there is no more dreadful punishment than futile and hopeless labor.

Myths are made for the imagination to breathe life into them. As for this myth, one sees merely the whole effort of a body straining to raise the huge stone, to roll it, and push it up a slope a hundred times over; one sees the face screwed up, the cheek tight against the stone, the shoulder bracing the clay-covered mass, the foot wedging it, the fresh start with arms outstretched, the wholly human security of two earthclotted hands. At the very end of his long effort, measured by skyless space and time without depth, the purpose is achieved. Then Sisyphus watches the stone rush down in a few moments toward that lower world whence he will have to push it up again toward the summit. He goes back down to the plain.

I leave Sisyphus at the foot of the mountain! One always finds one's burden again. But Sisyphus teaches the higher fidelity that negates the gods and raises rocks. He too concludes that all is well. This universe henceforth without a master seems to him neither sterile nor futile. Each atom of that stone, each mineral flake of that night filled mountain, in itself forms a world. The struggle itself toward the heights is enough to fill a man's heart. One must imagine Sisyphus happy.

One must imagine Sisyphus happy. In our absurd contemporary moment, I fear this has been corrupted into One must imagine Sisyphus collapse-averse. Pushing, straining, forgetting where he begins and the boulder ends, sweating, endlessly upward, forgetting if this is a loop of time or not, if there is a peak at all. The impossibility and resistance of collapse.

Camus reminds us: If the descent is thus sometimes performed in sorrow, it can also take place in joy. This word is not too much. In the midst of the entropic exhaustion of the universe, the narratives of linear, endless progress, collapse is our relief. The existential reminder of the entropic exhaustion of the universe, which fractals inside our bodies.

One must imagine Sisyphus collapse-aware. One must imagine Sisyphus happy. Each atom of that stone, each mineral flake of that night filled mountain, in itself forms a world. One must imagine Sisyphus fractal-ing little worlds of feeling within the body—that site of so many ontological cave-ins. I watch the rock roll. Watch, and then descend the slope into the underworld. There is an absurd, joyful curiosity.

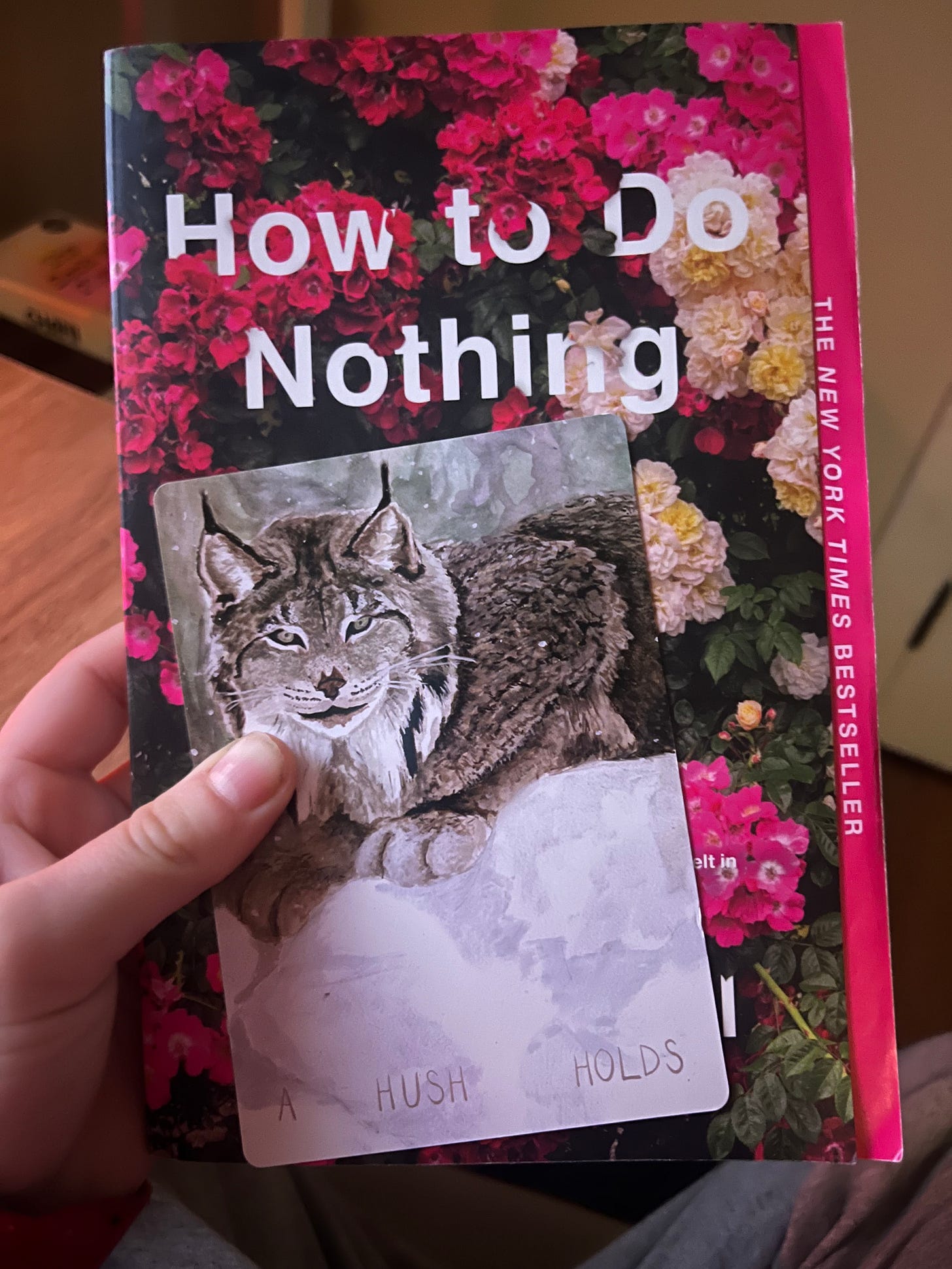

I’ve been contemplating the concepts of true rest and return lately. This is in part due to picking back up Jenny Odell’s How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy. I had begun reading the book a couple years ago, but put it down, ironically, because my attention was diverted elsewhere. I picked it back up after a recommendation from a new friend. There is so much truth in books finding you at the right time. In the midst of all this, the text resonates more deeply than it would have in any other time of my life.

The second chapter is titled “The Impossibility of Retreat.” Odell ponders the existential question that humans, throughout history, have been drawn back to again and again: do I leave, forever? Camus is pondering the same question: the question of philosophical suicide. Scattered throughout our digital platforms you will find this question reverberating in the void. The desire to leave. To run away and escape into the woods.

Odell agrees that these retreats and escapes are necessary, despite their eventual failures throughout history: the commune craze of the 60s, for instance. The beauty of the retreat lies in impermanence; not for a rejuvenated return to society for the purpose of restored productivity and continued “progress,” but as portals for wisdom that render the constructions of society absurd. To retreat and return, cyclically, and to exist in the wrong way, is what Odell calls “standing apart”:

Some hybrid reaction is needed. We have to be able to do both: to contemplate and participate, to leave and always come back, where we are needed.

To stand apart is to take the view of the outsider without leaving, always oriented toward what Is you would have left. It means not fleeing your enemy, but knowing your enemy, which turns out to not be the world—contemptus mundi—but the channels through which you encounter it day by day.

Standing apart represents the moment in which the desperate desire to leave (forever!) matures into a commitment to live in permanent refusal, where one already is, and to meet others in the common space of that refusal. This kind of resistance still manifests as participating, but participating in the “wrong way”: a way that undermines the authority of the hegemonic game and creates possibilities outside it.

I am reminded, again, of our Hermit year. Our year of “doing nothing,” while knowing the “nothing” is the key. Resisting the totality (and impossibility) of endless retreat and resisting the totality (and also impossibility!) of endless “progression”. The “doing nothing” as doing something, in the “wrong way.” As resting in the abundant gift that is mutual reciprocity and participation.

This, I know, is the function of The Hermit archetype. Yes, the hermit retreats, stands apart. But it always comes back. It always offers something up to the world, in its own way. It offers sage advice to the weary traveler, dripping in egg. It provides The Fool what it needs to continue.

I published my last piece immediately before my second diagnostic appointment. This was not planned, and I have to imagine it would not be recommended, but that morning I had entered a flow, and something in me just knew a piece wanted to come through. I wrote feverishly through the morning and published less than an hour before my appointment. Certainly not rest in the traditional sense; yet when I arrived at the appointment, I was energized. Perhaps this was from the release, or the flow, or the refusal to answer my brain’s desire for pre-appointment rumination. Instead, in its place, a strange meeting of relaxation and exhilaration.

My little regulating releases, my tiny catharses, have been: walking. Cooking. Baking. Tending. Listening. Reading. Repetition. Writing. I find when I am in flow, especially when I am writing, my yearning reverses on itself; I want time to slow down rather than speed up. On a day like today, that is the sweet spot: I want time to speed up and I want time to slow down, and I want time to extend out, like tendrils, from all sides of the body. Today I am writing, reading, baking, and walking. Later, though my body is tired and I will want to burrow in my writing, I will attend my Community Emergency Response Team (CERT) meeting.

I’m in the process of preparing and baking my second sourdough loaf. Anyone who has entered a Sourdough Phase knows that it is a fussy process. It is, after all, a living organism. There’s the creation and feeding of the starter, for one. The proper cultivation of it. The temperature, which will vary based on climate, season, and time of day. The specific weights and densities. And perhaps most daunting: the bulk fermentation process. It is as daunting as time, or patience. You can set a timer, follow someone’s instructions to a T, watch the dough rise for hours on end, and still get it wrong. You have to listen to the dough—learn to recognize what it is telling you. This, also, takes time. And patience. And repetition.

I am taking a class on “the necropastoral” with writer Gabriela Frank. Each week is delicious, gross, and delightful. Last week, we talked about the decomposition process. In one prompt, we were asked to freewrite from the positionality of various stages of decay. The prompt for fermentation:

Fermentation: In active decay, the fruit’s tissue becomes visibly colonized by microorganisms, often resulting in visible mold or rot. Fermentation occurs with tissues becoming moist, soft, and possibly smelly.

The first time I baked sourdough with my brand-new starter, I was impatient. It had been hours of waiting. I figured the dough had to be ready. The bread came out gummy, with barely any rise: under-fermented. In my impatience, I had not given the bacteria enough time to rise.

So much of under-fermentation is caused by a fear of over-fermentation: I’ll wait too long, and then I won’t be able to use it.

This second time, I over-fermented, leaving the dough to rise overnight. I did this on purpose, as I wanted to go to bed as opposed to checking it constantly. I have also heard that while over-fermented dough is not ideal, it is still a better outcome than under-fermented.

When I awoke this morning, it was airy, over-hydrated, and sticky. It looks ugly, but it’s not bad. The dough is bubbly, slippery, and will not hold its shape, but it will still taste good.

I had just put my sourdough in the fridge for a cold ferment, and was cleaning up the sticky mess on the counter. Sourdough, especially when over fermented, leaves its residue everywhere. When it dries, you’ll see the flour cement sticking to surfaces anywhere you look. The sink. The floor. The microwave. The coffee machine. The cat. Your hands. My devices buzzed—my diagnostician had sent me a message.

I don’t want to know. The thought came suddenly, urgently. I don’t think I’m ready. I don’t want to know.

I checked anyway.

It was a response to my own field notes: the additional evidence I had provided in one of my cyclical hypervigilant spurts. I had forgotten so much. I had withheld so much without knowing I was withholding, selected just another piece of hay in the stack instead of the critical needle. But there: she’d incorporated my notes into hers. A cheerful acknowledgment of my residue—not an answer to everything, but letting it know it’s welcome.

Each morning I pull Tarot cards, and two cards from the Abacus Corvus “Wild Chorus” Deck. This morning I pulled “A Hush Holds.” In the image, a lynx crouches, muscles coiled, atop a mound of snow. Importantly, the card’s description notes, we do not know what is under the mound, or what the lynx is preparing for. It is the spirit of both/and: rest and preparation. True rest in preparation, for it is the preparation that allows us to rest: both in its meditative assembling and in the assurance of knowing we are ready.

In CERT, we are preparing a “go bag” manual for residents of our town. What to pack to prepare for a time of emergency, when we have to leave quickly.

In Octavia Butler’s The Parable of the Sower, Lauren Olamina writes: God is change. She preps her own go-bag. She says, I intend to survive. When the time comes, she is ready. She has channeled that potential energy into a tool of survival. In the bag are various seeds, to plant in whatever new world exists post-apocalypse.

I was listening to a podcast today: “Navigating 2025: The Year of the Hermit w/ Jeff Hinshaw” on Edgar Fabián Frías’ “Your Art is a Spell.” Hinshaw speaks of the Hermit as “leaving behind society but not leaving behind humanity.” How when the Hermit goes underground or retreats, it does so through daily, intentional practice —and importantly, it returns. In the midst of change, we have our constants. Our practices of cyclical return and integration through connection with the natural.

In the episode, Frías and Hinshaw answer a question from a listener, who references Jambalaya: The Natural Woman's Book of Personal Charms and Practical Rituals by Luisah Teish. In the book, Teish writes, Your smallest altar is a cup of tea. In that sense, a go-bag could be an altar we prepare.

The Fool has a go-bag, of sorts as well as they prepare to jump off the cliff. Not a huge backpack, but a small bindle. Perhaps it was all The Fool had time to pack—and yet, it is somewhat enough. A portable altar, for resting as we go.

I recognize what I am doing now, writing you this letter, sending to it forward in time, is preparing a proverbial go-bag. Or more like a Fool’s bindle: it is scrappy, and I assembled it quickly. It was all I had time to pack. I am buying myself time for after I know, whatever that brings.

I wait, muscles coiled, go-bag prepped, hush holding, for whatever emerges. I intend to survive.

From me to you, forward in time,

Kelly

Annotation, 3/25/25: Reader, I still have no answers. Here with you, still, in the excruciating middle—though I’m beginning to understand why.

It strikes me as interesting that my body operates the same way in accordance with its needs, only recognizing them in their most extreme iterations. Or, in other words: too late.

From Rosalind Krauss’ essay “Reinventing the Medium.”

Sidebar: I am so sorry if this is meaningless jargon to you. I won’t dwell on it too long.

And let me reiterate: fuck mind-body dualism.

I was re-reading this newsletter when I realized I had made an error. In the initial iteration of this newsletter, the italicized portion of this paragraph did not exist. I had skipped over the crash—like my memory fragmented and the shard slipped out. I tend to write in disjointed fragments before letting them assemble themselves, and I must have thought I could come back and add the crash later—that I could bypass it somehow. I am always doing this.